What Is Inulin and Why Does It Matter

Inulin is a naturally occurring carbohydrate found in plants such as chicory root, Jerusalem artichoke, dandelion, and agave. It belongs to a group of soluble dietary fibres known as fructans — long or short chains of fructose molecules that the human body cannot digest (Roberfroid, 2007). Instead of being absorbed in the small intestine, inulin travels to the colon, where it serves as food for beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus (Kolida & Gibson, 2007).

Due to this selective feeding effect, inulin is classified as a prebiotic—a substance that promotes the growth of beneficial microorganisms while inhibiting the growth of pathogens.

Although inulin’s scientific use is relatively new, its presence in traditional diets is ancient. Indigenous peoples of North America roasted or boiled Jerusalem artichokes and camas bulbs — both naturally rich in inulin — while the ancient Greeks and Egyptians valued chicory and dandelion for their digestive properties.

In 18th-century Europe, chicory root became a popular substitute for coffee, but scientists later discovered that it was also a rich source of inulin. Since then, it has become the principal raw material for industrial inulin extraction, now used in functional foods such as yogurt, cheese, and baked goods (Roberfroid, 2007).

Inulin and Its Role in Yogurt Making

Inulin plays two roles in yogurt:

-

Technological: improves texture and viscosity by binding water and interacting with milk proteins. It gives low-fat yogurt a creamier consistency and reduces whey separation.

-

Nutritional: acts as a prebiotic that nourishes probiotic bacteria, helping them survive during storage and digestion (Kolida & Gibson, 2007).

Because the primary yogurt cultures (Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus) cannot ferment inulin directly, it functions mainly as a stabiliser and supportive ingredient rather than as a fermentation sugar.

The recommended level is 2–5 g per 100 g of milk, using long-chain inulin for thickness or short-chain (oligofructose) for sweetness and faster fermentation.

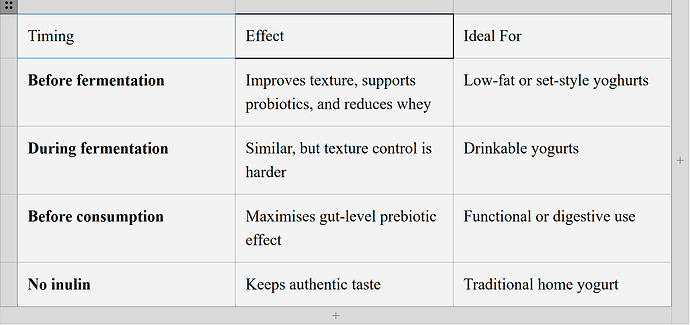

When to Add Inulin: Before, During, or After Fermentation

Adding a small amount before fermentation can enhance texture; adding a spoonful before consumption delivers maximum gut benefit (Rivière et al., 2016).

Which Bacteria Benefit from Inulin

While inulin is known to promote Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, recent studies show that it also supports a broader network of beneficial gut microbes (Scott et al., 2014; Rivière et al., 2016):

-

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii** & Roseburia spp.:** produce butyrate, an anti-inflammatory compound that nourishes colon cells.

-

Eubacterium rectale** & Anaerostipes spp.:** generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) for intestinal balance.

-

Akkermansia muciniphila**:** benefits indirectly from the metabolic by-products of inulin fermentation, supporting a healthy mucus layer.

Importantly, inulin is selective — most pathogens, such as E. coli or Clostridium difficile, cannot use it. Short-chain inulin acts in the upper colon, while long-chain forms reach deeper sections, providing balanced nourishment throughout the intestine.

Short-Chain vs Long-Chain Inulin

Inulin is a type of natural fibre made of tiny sugar units linked together. The length of the chain affects how it tastes, dissolves, and works in your gut.

-

Short-chain inulin (also called oligofructose): Has just a few sugar units. It has a slightly sweet taste and mixes easily into drinks or yogurt. Your gut bacteria ferment it quickly, allowing it to work efficiently, primarily in the upper part of the colon.

Found in: chicory root, garlic, onions, bananas, leeks, agave, and Jerusalem artichoke.

Suitable for adding gentle sweetness and promoting the growth of friendly bacteria quickly.

-

Long-chain inulin: It has many sugar units linked together. It isn’t sweet and doesn’t dissolve easily. It ferments slowly, feeding bacteria deeper in your gut and giving longer-lasting effects.

Found in: chicory root, dahlia tubers, burdock root, and globe artichoke.

Suitable for: making yogurt thicker and keeping gut bacteria healthy over time.

Inulin and Lactobacillus reuteri — The Science

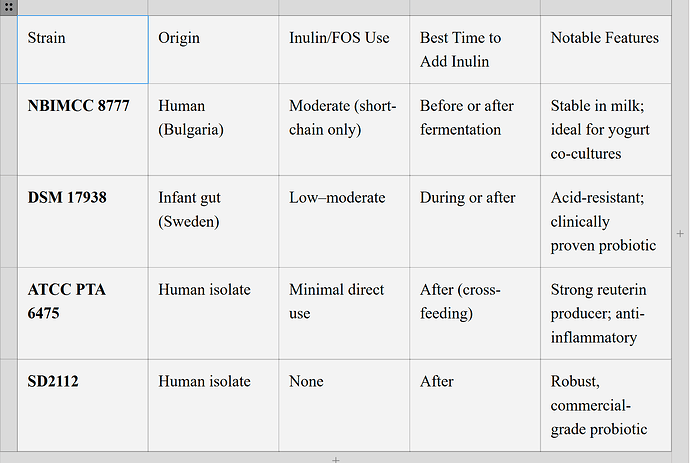

Among probiotic species used in yogurt, Lactobacillus reuteri (now Limosilactobacillus reuteri) stands out for its ability to colonise the human intestine and produce reuterin, a compound that suppresses harmful microbes. Yet, different strains vary in their response to inulin and fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS).

L. reuteri 8777

Registered at the National Bank for Industrial Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (NBIMCC, Bulgaria), strain 8777 is a human isolate used in research and food fermentation. It primarily ferments simple sugars, such as lactose and glucose, with limited use of short FOS (Short-Chain Fructo-oligosaccharides).

-

Adding inulin before fermentation: enhances texture but has a minor impact on growth.

-

Adding inulin after fermentation supports gut-level synergy by feeding companion bacteria, which, in turn, support L. reuteri 8777 colonisation (Saulnier et al., 2008).

DSM 17938

A derivative of ATCC 55730, this Swedish infant-origin strain is widely used in supplements. It grows well in milk alone but exhibits slightly better probiotic stability when inulin or FOS (Short-Chain Fructo-oligosaccharides) are present (Mu et al., 2018).

ATCC PTA 6475

Known for strong immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties. It does not directly ferment inulin, but benefits indirectly through cross-feeding relationships with bifidobacteria that ferment inulin (Rivière et al., 2016).

SD2112 (BioGaia Protectis)

Common in commercial probiotic products, SD2112 adheres well to the gut lining and tolerates acidic conditions effectively. It cannot ferment inulin but thrives alongside inulin-utilising species (Jäger et al., 2019; Pallin, 2018; Wall et al., 2007).

L. reuteri strains do not depend on inulin for fermentation but perform better in synbiotic systems where inulin-fed bacteria create metabolites that support their growth.

Should You Add Inulin when making yogurt at Home?

For home yogurt making, the answer depends on your goal:

-

If you value traditional authenticity, you don’t need inulin at all — milk and starter culture alone are perfect.

-

If you want thicker, low-fat yogurt, adding a small amount (1–2%) before fermentation improves consistency.

-

If you seek digestive support, stir a teaspoon of inulin into your serving.

Traditional yoghurts made for centuries across the Balkans, the Middle East, and Central Asia never included inulin, yet they produced healthy, resilient cultures. Modern science provides us with additional tools, not replacements for what already works.

Benefits and Limitations

Benefits

-

Strengthens probiotic survival and gut balance (Kolida & Gibson, 2007).

-

Improves creaminess and mouthfeel in low-fat yogurt (Roberfroid, 2007).

-

Increases calcium and magnesium absorption (Griffin et al., 2002).

-

Supports diverse gut microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids production.

Limitations

-

Excessive intake can cause mild bloating or gas (Roberfroid, 2007).

-

Overuse may lead to a too-thick texture.

-

Not a direct energy source for yogurt bacteria — lactose remains essential.

Traditional vs Modern Yogurt Philosophy

Traditional yogurt making is about simplicity: milk, starter, warmth, and time. Adding inulin or other fibres represents a modern “functional” approach — enhancing rather than replacing the natural process.

For the purist, there’s beauty in the unaltered balance of milk and microbes. For the innovator, there’s value in using prebiotics, such as inulin, to turn yogurt into a synbiotic — a living partnership of probiotics and their preferred food source.

Inulin bridges past and present. From the chicory roots once used by ancient cultures to today’s probiotic yoghurts, it represents both tradition and innovation. Used moderately, it enhances yogurt texture and supports beneficial bacteria, including Lactobacillus reuteri 8777, DSM 17938, ATCC PTA 6475, and SD2112.

However, inulin is optional: high-quality milk and a live starter remain the foundation of great yogurt. For home fermenters, authentic milk-and-starter yogurt is timeless; a spoonful of inulin at serving simply adds a gentle, modern twist.

References:

-

Griffin, I. J., Davila, P. M. and Abrams, S. A. (2002). Non-digestible oligosaccharides and calcium absorption in girls with adequate calcium intakes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(2), pp. 418–423.

-

Kolida, S. and Gibson, G. R. (2007) Prebiotic capacity of inulin-type fructans. Journal of Nutrition, 137(11), pp. 2503S–2506S.

-

Mu, Q., Tavella, V. J. and Britton, R. A. (2018). The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes, 9(4), pp. 353–364.

-

Roberfroid, M. (2007.) Inulin-type fructans: Functional food ingredients. Journal of Nutrition, 137(11), pp. 2493S–2502S.

-

Rivière, A., Selak, M., Lantin, D., Leroy, F. and De Vuyst, L. (2016). Modulation of the colonic microbiota by prebiotics and synbiotics: recent developments. Beneficial Microbes, 7(1), pp. 1–15.

-

Saulnier, D. M., Morrow, A. L., Gibson, G. R., Versalovic, J. and Macfarlane, S. (2008). Microbial cross-feeding and functional interactions among gut microbes. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 19(5), pp. 491–498.

-

Scott, K. P., Duncan, S. H., Louis, P. and Flint, H. J. (2014) Dietary fibre and the gut microbiota. Nutrition Bulletin, 39(1), pp. 36–41.

-

Jäger, R., Mohr, A.E., Carpenter, K.C., Kerksick, C.M., Purpura, M., Moussa, A. and Iosia, M. (2019) International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: probiotics and their mechanisms of action in intestinal health and performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 16(1), p.31.

-

Pallin, A. (2018). Improving the functional properties of Lactobacillus reuteri. Doctoral Thesis. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

-

Wall, T., Bath, K., Britton, R.A., Jonsson, H., Versalovic, J. and Roos, S. (2007) The early response to acid shock in Lactobacillus reuteri involves multiple stress response proteins.* Journal of Bacteriology, 189(23), pp. 7951–7957.